GPS + modeling reveal shrinking glacier

Photo: Jupiterimages/PHOTOS.com/Getty Images Plus/Getty Images

The Juneau Icefield Research Program (JIRP) calculates that thinning of Alaska’s Taku Glacier has increased from an average rate of 0.5 meter to 2 meters per year over the past two decades. Annual mapping by JIRP reveals the glacier’s thickness has varied from one year to the next, likely due to snow accumulation variability, but the overall current trend shows an annual net loss of ice.

“Taku is losing enough meltwater every day to fill an NFL stadium,” said Seth Campbell, JIRP director of Academics & Research.

At more than 800 square kilometers, Taku Glacier is the largest in the massive Juneau Icefield, making it vital to the study of climate change.

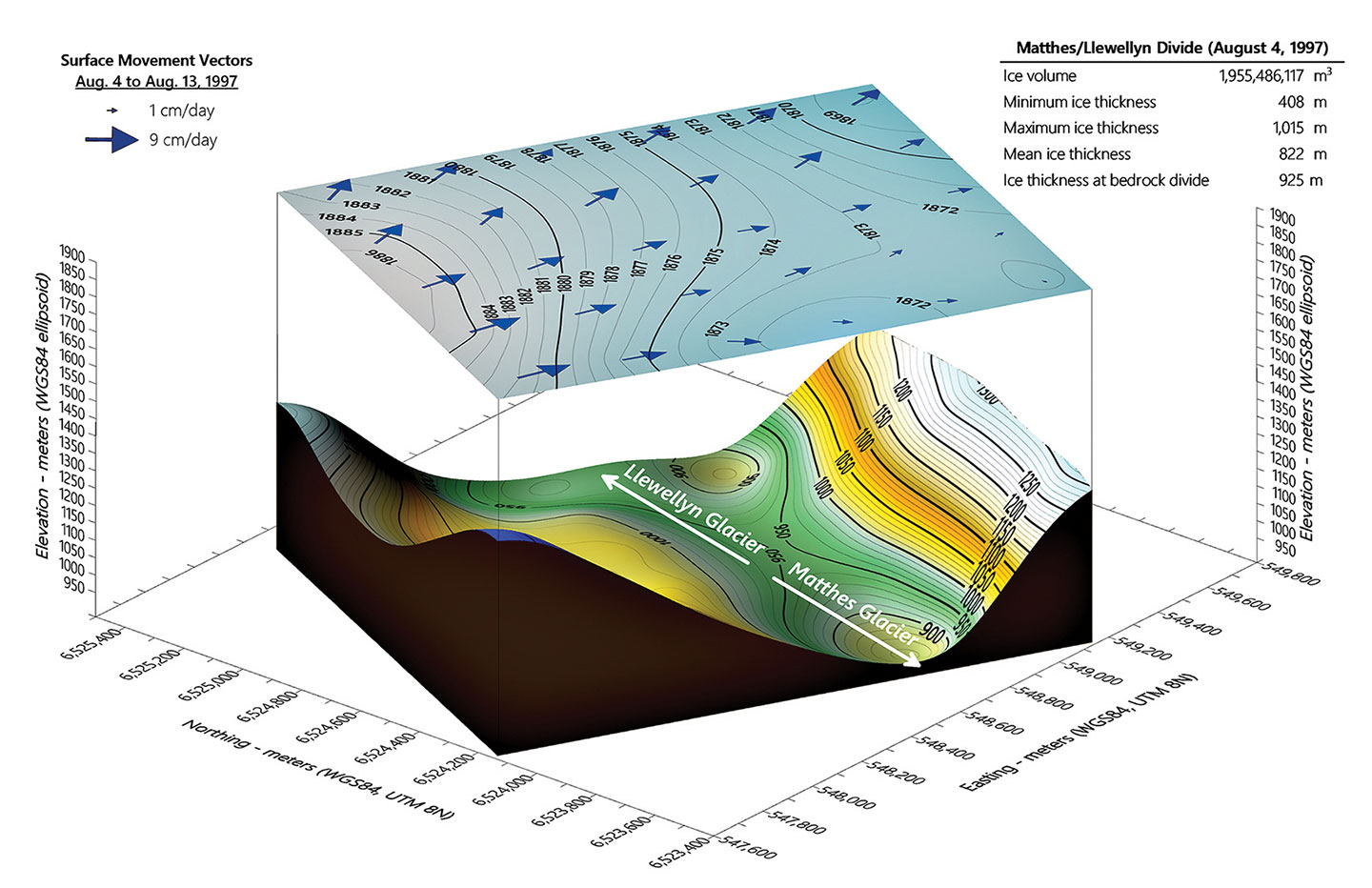

JIRP monitors the complex kinematics and mass balance of the Juneau Icefield — changes to ice velocity, snow accumulation and surface melting — to estimate whether the glacier is advancing or retreating over time. The team maps yearly GPS field measurements in Golden Software’s Grapher and Surfer modeling packages.

Image: JIRP/Golden Software

Straddling the Alaska-Canada border, the receding icefield plays multiple important roles in local ecosystems. For British Columbia, it provides fresh water, but for the Gulf of Alaska, increasing glacier meltwater can potentially harm the marine ecosystem and valuable fisheries.

JIRP research dates from 1946; the introduction of GPS in 1993 contributed significantly to annual summer fieldwork. Volunteers capture more than 1,000 GPS measurements at designated transect locations on the icefield each year to record glacial velocity and surface elevation changes.

Using Grapher, the team plots GPS “Z” elevation values across transects in 2D to generate thickness profiles. The scientists also input GPS field points for multiple transects from multiple years into the Surfer 3D surface mapping package to gain a sense of overall glacier volume change.

The primary revelation from the JIRP work has been a greater understanding of how and where the glaciers are changing, according to Scott McGee, JIRP Geomatics Program Lead. Until recently, glacial melt was assumed to occur mostly at lower elevations of the icefield, where temperatures are generally higher. However, McGee and the JIRP team have routinely discovered thinning occurring at all elevations of the icefield, including at the highest elevations of 1,900 meters.