Coral Reefs at a Crossroads: “Every coral we see is fighting”

This is a challenging time for coral reefs. Although they cover less than 0.1% of the ocean floor, coral reefs support 25% of all marine creatures. Collectively, they form one of the planet’s most important ecosystems. Their health is in jeopardy due to increased ocean acidification, rising temperatures, pollution runoff, and overfishing and other destructive fishing practices.

The news is not uniformly bleak. A global study of coral reefs that seemed wildly ambitious when it launched in 2014 suggests that some coral reefs are showing impressive resilience. Some could even be considered thriving.

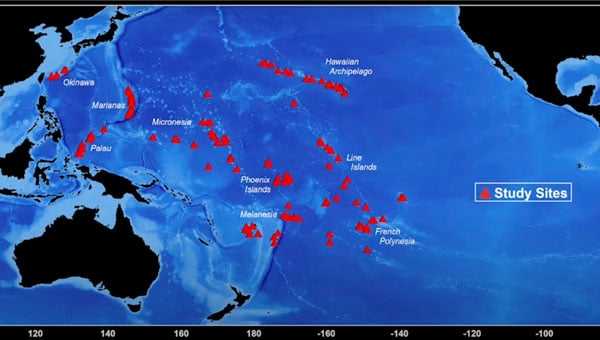

From the beginning, managing the study, dubbed the 100 Island Challenge, has depended on a creative and geographic approach.

Geographic information system (GIS) technology helped the 100 Island Challenge scientists define the initial scope of the study. Now it is allowing them to visualize and analyze the data they collect. GIS has also enabled the construction of environmental digital twins. In this case, the highly realistic and navigable 3D models depict many of the world’s major coral reefs, capturing flora and fauna in precise detail.

Reassessing Reefs

“I’m focused on coral reefs because it’s a great place to watch animals,” said Stuart Sandin, an ecology professor at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego. “Organisms are packed together, interacting with one another.”

Since the early 2010s, marine ecologists like Sandin have noted how reef health is indicative of a greater overall breakdown in ocean health.

“The timely issue was that we were seeing a ton of degradation,” he said. “It was no longer just a discussion about these ecological principles.” Coral health became a matter of global urgency that highlighted a possible tipping point, with coral decline contributing to biodiversity loss.

Sandin was drawn to the question of local and direct human influences, like overfishing and pollution. He realized that this was, at its roots, a spatial question and it was urgent. If humans were causing harm, changes could be made to reduce the impact. Analyzing the connection involved assessing the influence of humans on nearby reefs.

One of the earliest inquiries Sandin and his Scripps colleagues made involved the Line Islands, 11 atolls in the central Pacific Ocean, a thousand miles south of Hawaii. The mix of inhabited and uninhabited atolls belong to the Republic of Kiribati (pronounced “KIR-ee-bas”) and US territories.

Studies of the coral reefs near the uninhabited islands yielded positive results.

“The baseline ecosystems were everything we dreamt of,” Sandin said. “Tons of big sharks, big corals, clean water. We thought it was cool that those conditions still exist.”

When Sandin’s team turned to some of the Kiribati islands with small but growing human populations, the difference was stark. Human activity—particularly the modest amount of fishing done by residents of this small country—had degraded and even destroyed some of the reefs.

The results appeared to speak for themselves. Islands with no human presence had healthy reefs—those with people did not.

As Sandin looked at other islands around the world—including other more distant Kiribati islands—he discovered the strict dichotomy did not hold true. Some inhabited islands that had experienced many generations of fishing still had thriving coral ecosystems. The health of an island’s reef systems was not necessarily determined by human presence.

“I realized the human dimension was more than just binary,” Sandin said. “It wasn’t just presence versus absence. I knew we should start studying the variation of human use, where it works well and where it doesn’t.”

The Challenge Begins

A major challenge of studying ecosystems, even those as spatially concentrated as a coral reef, is the dizzying array of factors that affect their function. Sandin’s team defined 18 types of islands, based on such factors as the size of the human presence and the island’s geography.

The team members decided they should find five island examples of each of the 18 classifications, meaning the project was committed to studying 90 islands. Then they decided that adding 10 islands, bringing the total to 100, would give the study a more impressive pedigree. “We rounded up to make the T-shirts look better,” Sandin joked.

From the beginning, the 100 Island Challenge presented logistic hurdles. Sandin’s team had to research islands for possible inclusion, classify them, and maintain a globally dispersed atlas of candidates. The islands chosen are mostly concentrated throughout the Pacific, the Indian Ocean, and the Caribbean…